by Chris Russell, Contributor

Properly aging wine is a critical aspect of winemaking. Without some measure of aging, most wines would be rough around the edges and fall far short of their full potential. Aging wine is a complex enterprise, with different wines requiring different materials, techniques, and lengths of time to arrive at their peak. In this post, we’ll explore how a wine progresses from the end of fermentation to bottling and, at last, enjoyment.

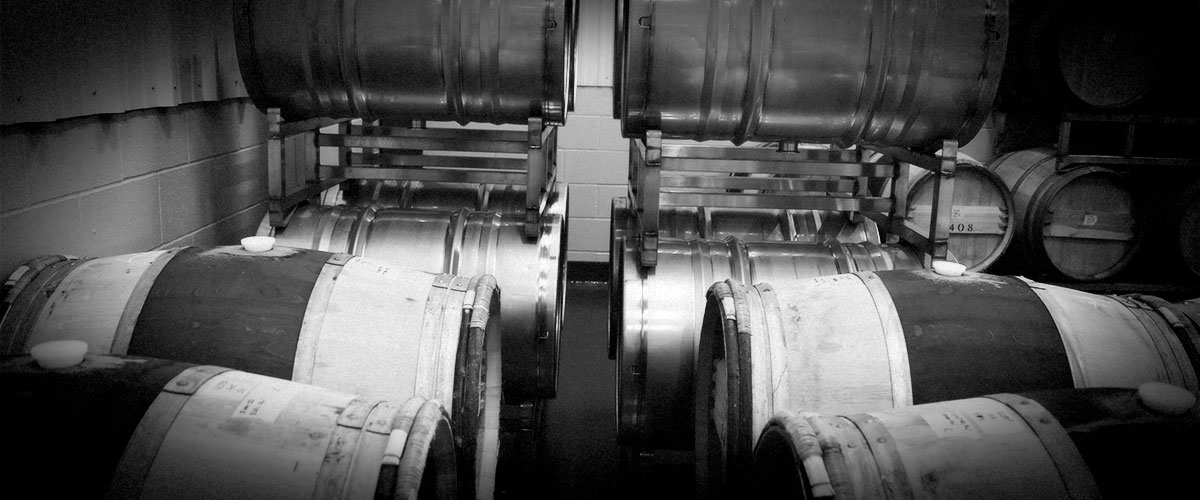

In the Barrel

Once wine has been fermented, it’s ready to be transferred—“racked” in winemaking lingo—to an aging vessel. This is typically an oak barrel, although other options exist, including stainless steel, amphorae, and concrete. Different materials have their application, depending on the desired qualities in the finished wine. Often, a young wine will be split into smaller lots that spend varying amounts of time in different aging vessels, which are then recombined (blended) later into a finished wine that possesses a complexity beyond the individual components.

Stainless Steel

Stainless steel is an airtight, nonreactive material that doesn’t allow the wine to react with oxygen, nor does it impart any aromas or flavors to the aging wine. Durable and easy to clean, stainless-steel tanks are great for winemakers as they can be used repeatedly for years. Because the wine is in an anaerobic environment, these vessels put wine into a suspended animation of sorts, preventing it from changing too dramatically while awaiting the blending or bottling stage. This anaerobic aging allows the wine to integrate aromas and flavors in a way that creates a seamlessness in the wine’s texture and body.

Oak

Oak enjoys a long tradition in winemaking. Oak barrels are slightly permeable to oxygen, allowing a little desirable oxygen ingress, which helps flavors and aromas to develop a more mature, complex character. New oak barrels are almost always toasted by fire to enhance the aroma and flavor compounds naturally present in the wood that are imparted to the wine, such as vanilla, caramel, and butterscotch. They also contribute wood tannins to the finished wine that can be softer and smoother than grape tannins and are often associated with spicy notes or creamy hints on the palate. Heavily toasted barrels can even impart such strong aroma and flavor components as coffee grinds or bittersweet chocolate to the finished wine’s aroma or flavor.

Different types of oak yield different flavor and aroma profiles. American oak tends to be more forward, with stronger, sweeter notes that have greater aromatic impact. French oak leans toward a more subtle impact that is mainly on the palate, with silkier tannins than American oak. Many winemakers—including here at 2Hawk—tend to prefer French oak, despite being more costly.

The age of the oak comes into play as well. Oak barrels may be used more than once, contributing less flavor and aroma to subsequent wines. After several uses, the barrel may not have any more aroma or flavor to give up, at which point it can be considered “neutral,” a vessel that will contribute little to no flavor or aroma to an aging wine but will still allow wine to age and develop in an aerobic environment.

Other Options

Winemakers can also choose alternatives to stainless steel and oak. One choice is a hybrid between the two: adding oak planks, or staves, to a stainless-steel tank combines some of the characteristics of both. Oak isn’t the only wood used for barrels, either. Acacia wood barrels are increasing in popularity, as are concrete aging vessels. Other materials, such as plastic or glass, have practical application for small-scale winemaking lots but are uncommon in larger-scale production.

Sur Lies

When a wine is finished fermenting, yeast cells die off and settle to the bottom of the fermentation vessel, where they become known as “lees.” Aging a wine in contact with these lees is known as aging “sur lies” (French for “on the lees”). When aging sur lies, the yeast cells gradually break down, releasing a variety of flavor and aroma compounds. Complex sugars called polysaccharides are also released, which can add to a perceived sweetness in the finished wine.

As importantly, the yeast also release proteins called mannoproteins, which can bind to tannins in the wine and thus decrease astringency while creating a richer, creamier, fuller mouthfeel.

Aging sur lies requires the application of another technique known as “bâtonnage,” which involves periodically stirring the settled lees back into the wine. Bâtonnage helps dissolve the compounds from the lees into the wine.

Aging wines sur lies is not an exact science. Some wines benefit more than others, and not all wines respond the same way in the same amount of time. Nearly all wines benefit from aging with the lees, which helps soften tannins and enhance flavors. As a general rule, however, wines that see extended barrel aging of more than one year, such as Malbec and Tempranillo, are not aged sur lies nearly as long as wines such as Viognier and Grenache, which generally only see eight to ten months of barrel aging. Our 2017 Darow Series Viognier is perhaps our favorite example: eleven months of aging sur lies and laborious bâtonnage created a wine that is as rich and opulent as it is delicate and complex.

Aging wines sur lies is not an exact science. Some wines benefit more than others, and not all wines respond the same way in the same amount of time. Nearly all wines benefit from aging with the lees, which helps soften tannins and enhance flavors. As a general rule, however, wines that see extended barrel aging of more than one year, such as Malbec and Tempranillo, are not aged sur lies nearly as long as wines such as Viognier and Grenache, which generally only see eight to ten months of barrel aging. Our 2017 Darow Series Viognier is perhaps our favorite example: eleven months of aging sur lies and laborious bâtonnage created a wine that is as rich and opulent as it is delicate and complex.

Blending to Perfection

As mentioned above, a finished, bottled wine is often the result of two or more lots aged in different ways and blended together to forge just the right balance of flavors and aromas the winemaker seeks. For example, our classic series spent six months aging sur lies, 85% in stainless steel and 15% in two-year-old French oak, before bottling. By contrast, our 2017 Muscat spent six months aging sur lies in stainless steel alone. Our decadent 2017 Darow Series Viognier spent eleven months split evenly between new and one-year-old French oak before aging for six months in stainless steel. There is no formula or recipe for this kind of winemaking. Only experience and instinct guide our decision making.

In the Bottle

Wines that have been bottled are generally ready to enjoy, but that doesn’t mean the aging process stops. In the bottle, wine will continue to age. Over time, fruity flavors tend to become more complex and subdued. White wines may gain golden, copper, or amber hues, while red wines tend to become less red and more brown. Tannins combine into larger, ever more complex chains, leading to a smoother and rounder texture and mouthfeel.

Some wines can benefit from some aging in the bottle, also called “cellaring,” if stored properly: around 55°F, 50–75% humidity, and away from bright light. Our 2016 Darow Series Malbec is a great example of a wine that will benefit from cellaring, while our 2018 Grenache Rosé is ready whenever you are.

Learn More

We hope you enjoyed exploring this fascinating and complex topic with us. Proper aging is a crucial part of our ongoing commitment to putting the very best wines we can in the bottle. If you’d like to sample the results of our aging process for yourself, consider paying a visit to our tasting room or browsing our selection online. Do you have any questions about our vineyard, our wines, or the winemaking process? If so, please comment below or reach out to us directly via our Contact page. We’d love to hear from you!

Meanwhile, if you’d like to know more about Rogue Valley wines, here are a few ways:

- Summer in the vineyard can be as challenging as it is rewarding. Read all about it in last month’s post, Summer in the 2Hawk Vineyard.

- Visit the tasting room to sample our current wines.

- Follow us on Facebook and Instagram to keep up with the latest happenings.