by Chris Russell, Contributor

Fermentation is the process by which grape “must” (a fancy winemaking term for unfermented grapes or juice) transforms into wine. During fermentation, yeast—our microbiological friends—convert grape sugars into alcohol. There’s a lot more than just alcohol production going on, though. Fermentation drives complex chemical reactions that affect the flavor, aroma, and even color of the finished wine.

Not Just Alcohol

At its simplest, fermentation is often described as the conversion of one molecule of glucose into two molecules each of ethanol (or ethyl alcohol) and carbon dioxide: C6H12O6 → 2C2H5OH + 2CO2. While that’s arguably the most important result, yeast are complex organisms that perform a wide array of biochemical processes in a fermenting wine.

Some of the compounds produced or affected by fermentation include:

- Esters: Esters are aromatic compounds that contribute delicate fruity, citrusy, or floral aromas to a young wine. They exist in must as precursors that are bound to sugar molecules. As the yeast consume the sugar, the esters are liberated and become volatile.

- Tannins: Present naturally in grape skins and seeds, tannins are antioxidant polyphenols that give wines dryness, astringency, and mouthfeel. The alcohol produced during fermentation enhances tannin extraction, while fermentation byproducts react with tannins, altering their structure, and, in turn, their perceived levels of astringency and bitterness.

- Acetaldehyde: Created by yeast in the penultimate step on the pathway to ethanol, low levels of acetaldehyde can enhance fruity aromas in wine. In high concentrations, acetaldehyde may yield unwanted bruised apple–like aromas and flavors. Acetaldehyde’s ability to catalyze tannin polymerization plays an instrumental role in the stabilization of red wine structure and mouthfeel.

- Anthocyanins: This highly reactive family of compounds in red grape skins gives red wine its color and antioxidative properties. These compounds polymerize in the presence of acetaldehyde to form a vast array of stable color components.

- Sulfites: As with ethanol, yeast produce sulfites during fermentation to fend off competition from other microorganisms. These natural sulfites can somewhat protect the wine from microbial spoilage and premature oxidation, but their levels are typically bolstered by winemakers after fermentation.

- Amino acids: Unfermented grape juice, or must, is rich in nitrogen-containing amino acids. Yeast consume most of these amino acids during fermentation, using the nitrogen to construct proteins and amino acids necessary to live and reproduce. Amino acids are the most important family of compounds in yeast nutrition and health.

From Many to One

The sweet, nutrient-rich must is an ideal medium for growing diverse species of yeast during the fermentation process. Naturally present yeast may include the familiar Saccharomyces, found in bread and beer, as well as more exotic genera such as Candida, Kloeckera, and Hansenula. As a result, the beginning of fermentation involves a lot of biodiversity, with many different types of yeast competing for resources. If allowed to ferment, each type of yeast leaves behind its own particular signature of flavor and aroma compounds.

Since not all yeasts are suitable for making wine, many wineries employ sulfites to suppress the activity of wild yeasts before fermentation, followed by inoculation with a commercially developed, cultured strain of Saccharomyces yeast. While this usually yields a predictable fermentation dominated by one particular variety of yeast, it doesn’t leave a lot of room for the natural microbiological diversity of the vineyard to shine through.

At 2Hawk, we prefer to take a gentler approach, encouraging the growth of desirable yeast found in our vineyard. These naturally occurring yeasts contribute a subtle, nuanced complexity to the finished wine that reflects the unique character of the Rogue Valley and our vineyard in particular.

As fermentation progresses, some species of yeast begin to rapidly convert the natural sugars present in the must into carbon dioxide and ethanol, or ethyl alcohol. Produced as a defense mechanism, few species of yeast can tolerate even moderate levels of ethanol. At around 4–5% ABV, or alcohol by volume, many of the yeast species present at the start of fermentation—like the Candida mentioned earlier—die off. As ethanol levels continue to rise, one strain—Saccharomyces—emerges as the victor of this fierce competition and embarks on fermenting the wine to dryness.

Influencing Fermentation

Various types of yeast make their own individual contributions to a fermenting wine, but fermentation is influenced by other factors as well.

Sugar Content

The higher the initial sugar content of the must, the more alcohol will be present in the finished wine—if allowed to ferment to dryness. More alcohol means a tougher job for the yeast, making monitoring yeast health important: unhealthy, stressed yeast are more likely to produce undesirable flavor and aroma compounds.

Fermentation Temperature

Fermentation temperature is also crucial. Lower temperatures preserve fragile, volatile aromatics in the wine, retaining a more “fruity” character. If temperatures are too low, however, yeast work slowly—or they may have difficulty fermenting all of the sugar. Higher temperatures allow for better grape skin tannin extraction but tend to drive off fruity flavors and aromas. If temperatures are too high, yeast may work at a frantic pace, producing undesirable flavors and aromas along the way. At the extreme upper end of the temperature range, yeast can even generate so much heat they die, which can impart an unpleasant “cooked” character to wines.

Finding the right fermentation temperature is all about balance. Red wines are typically fermented at the warmer end of the spectrum—between 70 and 85 degrees Fahrenheit—to take advantage of better tannin extraction. White wines are more often fermented at the cooler end of the spectrum, around 45 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit. Because fermentation is an exothermic process (i.e., it generates heat), winemakers must often take steps to actively control fermentation temperatures, particularly in large batch fermentations of several tons. At 2Hawk, we tend toward small batches, allowing for better passive cooling and reduced needs for active temperature control systems.

Fermentation Vessel

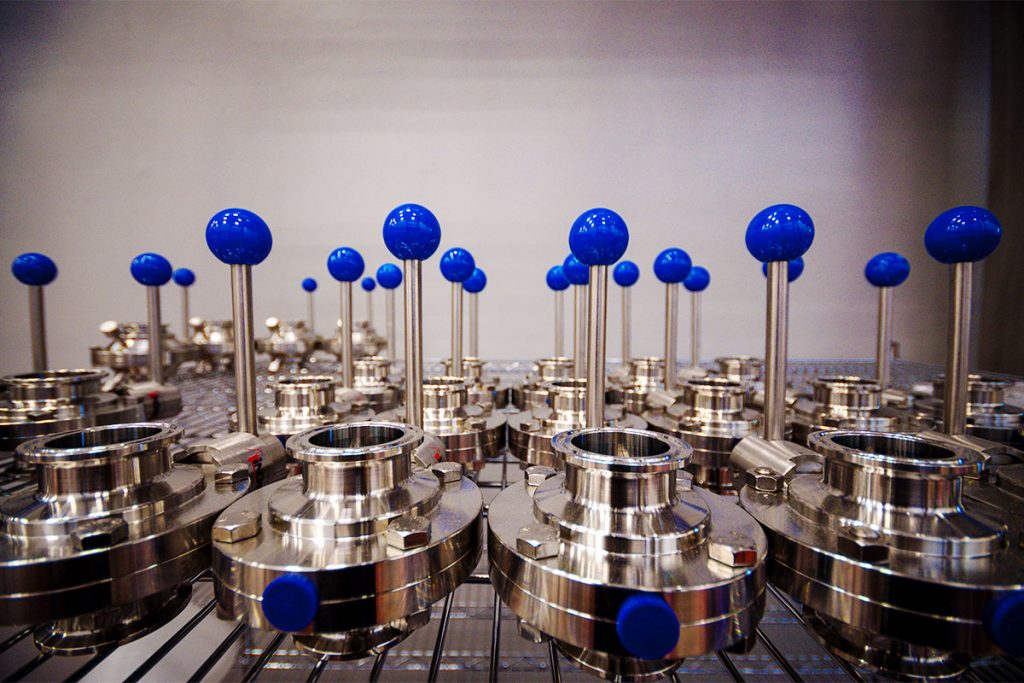

In a winery, fermentation occurs in a fermentation vessel, where yeast is allowed to complete its work. Different fermentation vessels can influence how fermentation proceeds as well as the finished wine. Oak, for example, allows for gradual oxidation of the juice and wine, while the wood usually softens the impact of tannins and acid, resulting in a rounder wine with a distinct character. Stainless steel is highly nonreactive, making for bright, clean, and crisper wines. Concrete fermentation vessels can leave behind a subtle mineral character in wines while permitting a little desirable oxidation. Clay vessels, a traditional choice making a comeback in recent years, enable some oxidation while being neutral or slightly earthy in terms of flavor contributions. The more porous the vessel, the more oxidative the conditions.

In a winery, fermentation occurs in a fermentation vessel, where yeast is allowed to complete its work. Different fermentation vessels can influence how fermentation proceeds as well as the finished wine. Oak, for example, allows for gradual oxidation of the juice and wine, while the wood usually softens the impact of tannins and acid, resulting in a rounder wine with a distinct character. Stainless steel is highly nonreactive, making for bright, clean, and crisper wines. Concrete fermentation vessels can leave behind a subtle mineral character in wines while permitting a little desirable oxidation. Clay vessels, a traditional choice making a comeback in recent years, enable some oxidation while being neutral or slightly earthy in terms of flavor contributions. The more porous the vessel, the more oxidative the conditions.

In addition to the fermentation vessel’s material, the shape and size of the vessel can be an influential consideration. Smaller fermentation vessels have more surface area for a given mass, meaning they can more easily shed excess heat from fermentation. Vessels with a rounder shape aid convection currents in the fermenting wine, facilitating fermentation by keeping temperatures uniform and yeast in suspension.

After Fermentation

Most of the time, fermentation is complete when yeast have consumed all the sugar they can, usually meaning the wine is fermented to dryness. Most of the yeast will die at this stage, gradually settling to the bottom of the fermentation vessel where they become known as “lees.” Depending on the wine style and winemaker’s preferences, the wine may be allowed to rest on the lees for some time, or it may be “racked”—transferred—to another vessel to begin the aging process without the yeast lees. The presence of yeast lees can have a profound effect on the aroma, flavor, and texture of the wine as it ages.

Learn More

We hope you enjoyed getting an inside look at this complex but essential aspect of the winemaking process. For a more general overview of winemaking, including what happens before and after fermentation, take a look at our earlier blog post, How is Wine Made? Can we answer any other questions you have about making or tasting wine? Please let us know! We’d be happy to help.

Meanwhile, if you’d like to learn more about Rogue Valley wines, here are a few ways:

- Read our Fall 2018 Harvest Wrap-Up to see why we’re excited about our 2018 vintage!

- Visit the tasting room to sample our current wines.

- Follow us on Facebook and Instagram to keep up with the latest happenings.

I began the fermentation process at a 70* temp. Then the temperature dropped to the 40’s. I left the batch undisturbed as per the kit instructions. However, I did check for expansion. There was hardly any. Today is the 11th day but for the last 3 or 4 days I noticed it was bubbling tiny bubbles and needs “burping” regularly. Should I let it work for a couple more days? The temperature is still very cold. 40* range.

Hi Roc,

Most wine yeast will work very very slowly, if at all, in that temperature range. You’ll probably want to start by checking the sugar content of the must, either using a hydrometer or just by taste. See if it’s obviously sweet or far from your expected finishing gravity. If so, you’ll want to move the fermenter somewhere warmer, at least 60-65F, give the fermenter a gentle swirl to coax yeast back into suspension, and let it work for at least a few more days. Make sure you have a means to release pressure from the fermenter aside from manual burping, as a vigorous fermentation can easily cause sealed containers to explode.

If there’s no sugar left, the bubbles you’re seeing could be the result of malolactic fermentation, which produces smaller, finer bubbles than alcoholic fermentation. You will want to either let it complete, or stabilize the wine according to the kit’s instructions.

If you have any additional questions, please feel free to run them by Kiley, our Winemaker. I’ll pass along his contact info via email. Happy fermenting, and cheers!